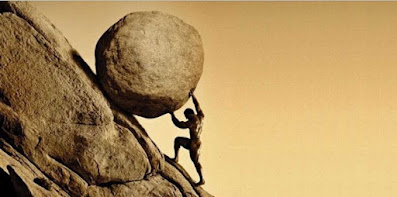

According to the Greek myth, Sisyphus is condemned to roll a rock up to the top of a mountain, only to have the rock roll back down to the bottom every time he reaches the top. The gods were wise, (Albert) Camus suggests, in perceiving that an eternity of futile labor is a hideous punishment.

Spark notes: The Myth of Sisyphus

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks.

He concludes that all is well.

This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart.

One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Albert Camus; The Myth of Sisyphus (pdf here)

In Albert Camus' book, The Stranger (aka The Outsider in Europe), after the main character's arrest for murder and while awaiting execution:

"...the whole problem was: how to kill time. After a while, however, once I’d learned the trick of remembering things, I never had a moment’s boredom.

Sometimes I would exercise my memory on my bedroom and, starting from a corner, make the round, noting every object I saw on the way. At first it was over in a minute or two. But each time I repeated the experience, it took a little longer.

I made a point of visualizing every piece of furniture, and each article upon or in it, and then every detail of each article, and finally the details of the details, so to speak: a tiny dent or incrustation, or a chipped edge, and the exact grain and color of the woodwork.

At the same time I forced myself to keep my inventory in mind from start to finish, in the right order and omitting no item. With the result that, after a few weeks, I could spend hours merely in listing the objects in my bedroom.

I found that the more I thought, the more details, half-forgotten or malobserved, floated up from my memory. There seemed no end to them.

So I learned that even after a single day’s experience of the outside world a man could easily live a hundred years in prison. He’d have laid up enough memories never to be bored.

Philosophy

Albert Camus

Albert Camus

No comments:

Post a Comment